- MTR to Kat Hing Wai (吉慶圍) Walled Village

- Walk to Ping Shan Heritage Trail (屏山文物徑)

- Walk to Hong Kong Wetland Park (香港濕地公園)

- MTR to Lok Ma Chau (落馬洲) Village

- Bus to Tai Fu Tai (大夫第) Qing-era Mansion

- MTR accidentally to Lo Wu Station (羅湖站)

- I accidentally took the East Rail Line (東鐵綫) instead of the West Rail Line (西鐵綫) and then accidentally took the train to the Lo Wu terminus instead of the Lok Ma Chau terminus (落馬洲站) needed to get to Lok Ma Chau Village

- MTR back to Sheung Shui Station (上水站)

- MTR to Lok Ma Chau Station (落馬洲站)

- I then realized that Lok Ma Chau Station was located in the middle of the so-called Frontier Closed Area between Mainland China and Hong Kong, meaning that all exiting passengers had to pass through customs into Mainland China. I had heard that Lok Ma Chau was a crossing-point into the Frontier Closed Area, but I didn't realize there was no physical way of getting to Lok Ma Chau village through the MTR Station!

- MTR back to Sheung Shui Station (上水站)

- Bus (KMB Route Number 176) towards Tin Tsz Terminus (天慈終站)

- Ping Shan Heritage Trail (屏山文物徑)

- MTR from Tin Shui Wai Station (天水圍站) to Kam Sheung Road Station (錦上路站)

- Kat Hing Wai Walled Village (吉慶圍)

- MTR from Kam Sheung Road Station (錦上路站) to Tsuen Wan West Station (荃灣西站)

- Get lost and then eventually find Sam Tung Uk Museum (三棟屋博物館)

An overall map of today's travels

A map of my wandering around to find Sam Tung Uk Museum

Here come the pictures...

Banyan trees are pretty culturally ubiquitous across southern Chinese and Southeast Asian cultures, but I've never actually knowingly seen one up close before. I snapped a few shots of some on HKUST campus before leaving.

So here is a shot I took at the Lo Wu Station crossing into Mainland China, just before I realized that it wasn't just AN exit from the station but the ONLY exit. Apparently, the demand for Hong Kong milk powder in Mainland China is so high that it's now apparently illegal to be carrying "excessive powdered formula"!

These are the idyllic views around Lo Wu Station - green farmer's fields framed with trees and ringed with mountains. This is somewhere in the extreme north of the New Territories, probably in the buffer zone with Mainland China. I'd imagine that Hong Kong used to look something more like this before the rapid urbanization that led to the eradication of its rural farm villages.

And here is a view of the crossing bridge between Hong Kong and Shenzhen near Lok Ma Chau. If you look very closely and zoom in a lot, you can see that it is already packed with people by this time (around 11:00am).

As I mentioned earlier in this post, I went to Lo Wu Station first, intending to go to Lok Ma Chau. When I doubled back to Lok Ma Chau, I realized I couldn't walk out of the station without crossing into Mainland China. So, I had to rewrite my plans and head over to the Ping Shan Heritage Trail, which is situated near Yuen Long in west New Territories. I decided to take the more direct bus route (KMB route 176) rather than the circuitous MTR route. I got off at the Tin Tsz Terminus, ate lunch at the Cafe de Coral (大家樂) - which has a startlingly similar menu to the canteen at HKUST - and then walked to the Ping Shan Heritage Trail. Here are some pictures of the trail:

Here is a shot of the Ping Shan Heritage Route area south from Tin Shui Wai MTR. In stark contrast with the area north of Tin Shui Wai, the southern area almost completely consists of the few-storey residential buildings in walled compounds favoured in Hong Kong's villages (村). I often see these Hong Kong village houses whenever I take the 11M minibus to Hang Hau from HKUST. The area north of Tin Shui Wai, on the other hand, consists almost solely of the super-high-rise apartments popular in the suburban (don't know if that's a term in Hong Kong) regions like Tseung Kwan O.

Anyways, here is the first stop of the Trail - the Tsui Sing Lau Pagoda (聚星樓). The sign on the door said it was closed due to meals (it was about 1:00pm) so I moved on

The initial reaches of the trail consisted of car parks, loading areas, and residential buildings. Combined with the fact that there was scant signage on the route itself, I found myself getting very lost.

Eventually, though, I found the second checkpoint of the route - the Shrine of the Earth God (社壇). I initially ignored it, but then considering the fact that an elaborate altar was built for two stones, I eventually realized its significance.

Here is the third checkpoint, the Sheung Cheung Wai Old Village Wall (上璋圍). These are the well-preserved remains of the old village wall of the Sheung Cheung Wai Walled Village.

After searching for some time, I finally found the fourth checkpoint, the Yeung Hau Temple (楊侯古廟), which is a temple dedicated by the old Tang (鄧) clan of Hong Kong to a meritorious general who accompanied the two last boy emperors of the Song Dynasty as they fled to Hong Kong in the final days of the Song Dynasty.

And I set off again to actually enter the village around the Ping Shan Heritage Trail, trying to get my bearings:

Hmmm... this palm tree looks like one of those that line the entrance to HKUST. I found it interesting that most of the roots seemed to be coming out of the ground and yet the tree was still standing upright.

The seal-script character 鄧 (Tang) was on the wall to one of the enclosed residential buildings - I knew I was in the right place.

Finally, after some wandering around the village, I came upon one of the unscheduled stops of the Heritage Trail - Yan Tun Kong Study Hall (仁敦岡書室). Like most study halls in Hong Kong, as I later found out, Yan Tun Kong Study Hall doubled as both a place of ancestor veneration as well as a place of education for the imperial examinations. As the Tang clan in Tsuen Wan was rather wealthy, they could afford a separate building to house their ancestral tablets (believed to contain the souls of the deceased ancestors) as well as a place to educate their youths for the imperial examination (which held high prestige for aspiring Chinese literati.

The doors of the study hall are opened by the lone security guard watching over the building.

This sign tells of a major restoration of the building completed in the Qing Dynasty.

In fact, the entire building has undergone major restoration after it was declared an archeological site of importance by the Hong Kong government (I think it was in 2009). Most of the recent additions (such as plaster over the original brick) and damage over time (like the deterioration of the wooden plaques) were redone by modern archeologists.

Here is one of the two side rooms, which acted as accommodations for visiting scholars.

Here are some shots of the ancestral tablets located in the ancestral hall at the back of the building.

Eventually, I made my way back to the main Ping Shan Heritage Trail and arrived at the fifth checkpoint - the Tang Ancestral Hall (鄧氏宗祠), built in 1273 by the original Tang clan ancestors who arrived in Hong Kong with the fleeing Song Dynasty boy emperors.

I took some pictures of the door goods painted on the outside of each door.

Here is a modern metal plaque containing a list of the Tang clan members that achieved success in the imperial examinations - a very prestigious achievement among high-class Chinese before the examination was abolished upon Hong Kong's handover to the British.

Here is a shot at the unique root support system used in traditional Chinese architecture.

The side rooms of the ancestral hall are still used for social gatherings and meetings by the Tang clan. You can see the drums on the left (presumably for festivals) and the stacked plastic chairs on the right (presumably for clan meetings and gatherings).

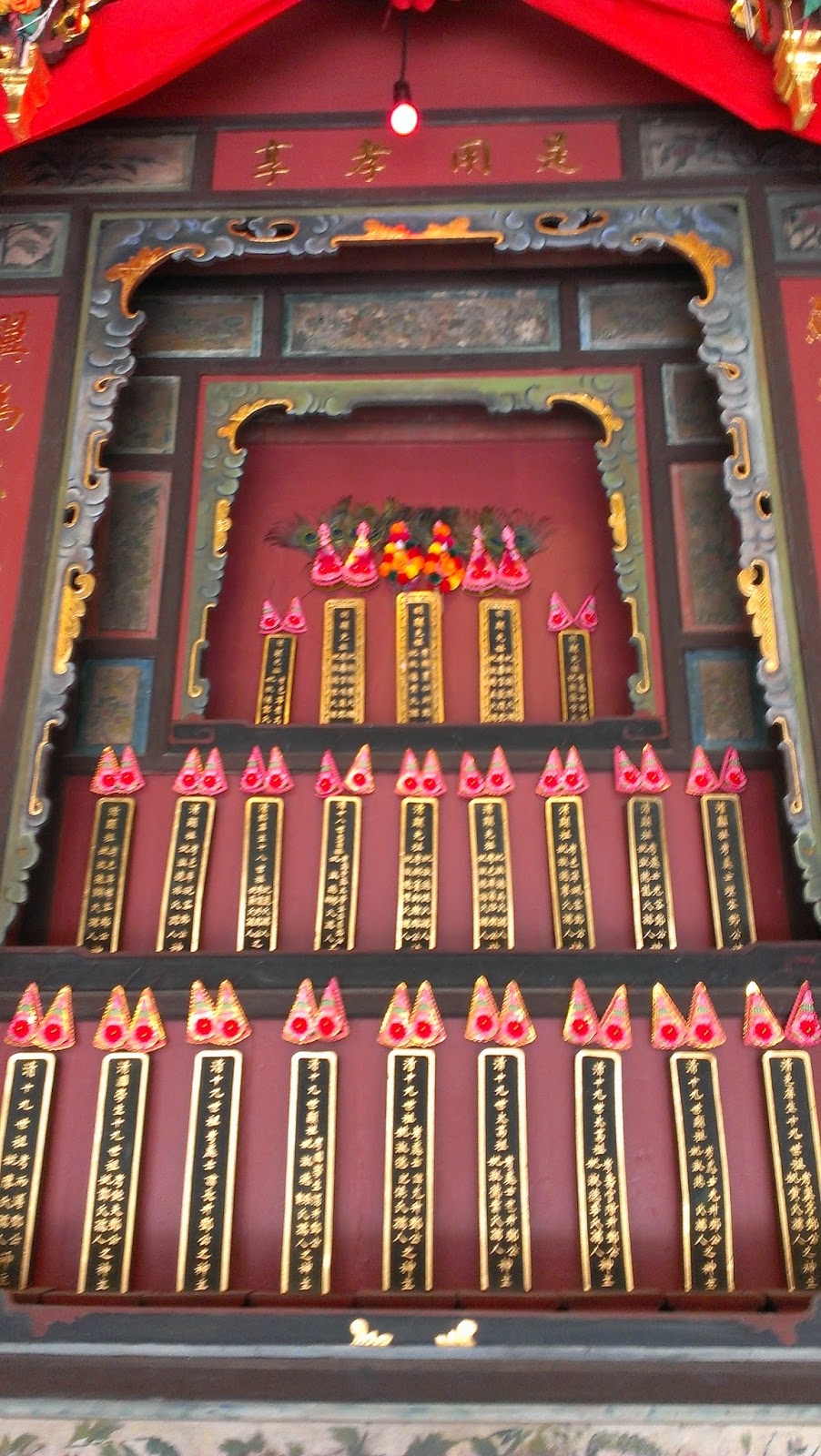

Here are the Tang clan ancestral tablets in the Tang Clan Ancestral Hall.

The Chinese character 考 (filial piety) adorns the right side of the ancestral tablets altar - it is truly symbolic of traditional Chinese thought, which had always centred the social order of China on the family. Indeed, the continued occupation and restoration of the Tang Ancestral Hall by the descendants of the original Tang Clan members serves as a reminder of the importance of the family and one's ancestors to Chinese culture.

Here is a gap between two Ancestral Halls in the village.

Next was the Yu Kiu Ancestral Hall (愈喬二公祠), which was built in the 16th century by two 11th-generation Tang clan members.

Here is a birthday tapestry to commemorate the 60th birthday of a prominent Tang clanswoman.

The Yu Kiu Ancestral Hall also has its own Tang clan ancestral tablets - I wonder if the ancestors worshipped in the different ancestral halls are the same...

The seventh checkpoint was Kun Ting Study Hall, which was purpose built for the education of the Tang clan youth for the imperial examination.

Adjacent to the study hall was Tsing Shu Hin (清暑軒), a guest house used by the Tang clan for visiting scholars and dignitaries.

The entrance was decorated with plaques honouring the Tang clan members who achieved notable successes in the imperial examination.

And here are some excellent explanation boards on the Chinese imperial examination system, the first civil service system in the world to select government officials based on merit as opposed to wealth or descent.

Here is an old visitor's bedroom:

Peering into the Sheung Cheung Wai doorway that I passed by earlier...

I then took the MTR to Kam Sheung Road Station. Here is the wonderful scenery around the station, with mountains capped with misty clouds in the distance:

While walking to Kat Hing Wai, I noticed some of the village compounds had traditional Chinese features mimicking the style found in the buildings on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail:

Finally, after some confused searching in vain for signs pointing to "Kat Hing Wai", I finally found it! It's a large walled compound with houses within it arranged in a rectangular grid pattern. Somewhat coincidentally, it was also settled by Punti (see last Sunday's post for more information) people belonging to the same Tang clan from the Ping Shan Trail. Originally, the houses were built in the traditional courtyard style but now the houses in the walled village are almost exclusively in the Westernized Hong Kong style. Nonetheless, the buildings still follow the rectangular grid format of the original village.

The entire village is centred along a main axis that runs from the entrance gate to the temple at the rear.

Here is a view of one of the side alleys - one navigates the walled village by selecting one of many side alleys from the central path.

Here is a view of a traditional altar in one of the homes

There are a lot of cats in Kat Hing Wai - I'm not sure if they have owners or are strays.

Here is the temple at the rear of the village:

A view of the entrance from within the village.

What truly surprised me was that some of the homes had the doors flung wide open. These villagers sure must trust each other (and the occasional nosy tourist)!

A reminder of the often violent past faced by the Hong Kong settlers, the watchtowers and thick walls of Kat Hing Wai were pivotal for its effective defence against bandits, rival clans, and prowling tigers.

As I walked over a bridge back to Kam Sheung Station, I shot this photo of an empty artificial river bed, apparently abandoned to the weeds.

This shot highlights another specimen of a phenomenon very prevalent in Hong Kong - blatant religious messages. The message on the building reads 耶穌説:我是世界的光 (Jesus said: "I am the light of the world"). In Canada, such an obvious religious message would probably give rise to angry citizens, protests, and the eventual forced removal of the sign. But in Hong Kong, they are commonplace and no-one even minds. Both societies are officially secular, but I think that this shows something about the attitude of society towards religion. Is the so-called "secular" society actually tolerant of all religions, or merely hiding their presences from the public sphere?

Eventually, after some more wandering around Tsuen Wan, I finally arrived at Sam Tung Uk Museum (三棟屋博物館). Originally, I had cached an offline map of the Tsuen Wan area on my Google Maps app, but it went temporarily buggy. It was only when I reached a 7-11 that I got some free Wifi and was able to reset my bearings. Then, I had to use some less technology-dependent navigation techniques to find my way (e.g. using shadow direction and looking for major street names)

After my earlier encounter with a banyan tree at HKUST, I identified this tree in front of Sam Tung Uk as potentially another banyan tree.

Anyways, Sam Tung Uk is, unlike Kam Hing Wai, a former walled village that was built in 1786 by members of the Chan clan of Hakka heritage who originated from Fujian province. My own paternal ancestors belonged to the Chan clan of Taishanese heritage, so I'm probably unrelated to these Chans! In 1980, the Hong Kong government was rapidly developing the Tsuen Wan region into a major satellite town and moved all the residents of Sam Tung Uk Village to a new site to the northeast. The Chan clan agreed to restore the abandoned village as a museum. Note how the actual village compares to the mock village showcased in the Hong Kong Museum of History (see last Sunday's post).

The entire museum consists of a central section with the ancestral hall, assembly hall, and entrance hall (a traditional structure even seen in the Tang clan ancestral halls) as well as flanking living quarters on the sides.

I had a feeling that I'd seen this message before - 祖德流芳 (Google translates it as "Jude Fame", so I'm pretty sure my translation - "the virtue of the ancestors flows fragrantly" - is better). Now, I realize that I'd seen it in the Tang Clan Ancestral Hall back in the Ping Shan Heritage Trail.

One of the cool things about the Sam Tung Uk Museum is that it is a museum - thus they have mock-ups and actual specimens of period farming implements. Often, many of the learning materials and information seemed geared towards children but it was still very informative. For example, they have a winnowing machine that you are actually allowed to operate.

And here is the kitchen, using the original stove and chimney. Here, the activity sheets ask the visitors to compare period cooking equipment to modern ones.

A period set-up of a village meal table. This was the only place in the museum where, according to the sign, the place was "sanitized every 1-2 hours"... I wonder what that means.

A candle holder, basket, and tea cup.

A traditional village bedroom, complete with spitoon (or is it a chamber-pot), ceramic pillow, fan, mosquito net, slippers, and leather chest.

As it is a museum now, Sam Tung Uk looks absolutely pristine compared to the rather dirty conditions found in Kam Hing Wai. Indeed, the restoration team put much effort to restoring the buildings to their original appearance, resulting in walls that were probably never this white since the day they were plastered.

More period farming implements, gathered by Hong Kong researchers who hunted down the farmers who were rapidly disappearing from Hong Kong:

A historic baby cradle and baby chair (complete with child-proof restraints) were placed in this bedroom!

Here is the bedroom of the eldest son in the Tang clan, located at the prominent location adjacent to the ancestral hall area (I think):

The Chan clan ancestral tablets were in the ancestral hall.

One of the museum houses contained an exhibit dedicated to showcasing traditional Hakka marriage artifacts, with the bride's sedan chair and containers for the marriage presents:

And as a tribute to the momentous role played by agriculture (especially rice cultivation) in Hong Kong's history, the museum held a series of information exhibits on the process of rice cultivation. On a side note, Sam Tung Uk was a farming village and used to have an optimal feng shui (風水) environment with its rice fields in front, forests surrounding the sides and rear, and mountains behind the forest.

Personally, I have long been interested in the process of rice cultivation, so I'll summarize what the exhibits say. First, the process begins in the spring, when the empty fields are broken up by farmers using oxen-drawn plows. Then, the fields are flooded by using irrigation channels. The rice seedlings are germinated in water, planted in a seedling nursery, and then transplanted by farmers bent-over-back into the watery fields.

In the summer, most of the work is centred around fertilizing the rice crop and ensuring that the rice crop is protected against weeds. During this period, the originally flooded fields slowly begin to dry up.

In the autumn, the fields have dried up and the rice is ready for harvesting. The farmers go to the fields and cut the rice plants at their stems with sickles. The rice grains are shaken off by threshing and collected while the stems are collected in bundles and used for other purposes (probably building materials or fertilizer). The rice grains are separated from the chaff by using a winnowing machine and then the rice is ready to be cooked for consumption.

By contrast, the weather is too cold in the winter for any productive agricultural activities, so the villagers would often repair farming implements and store the harvested grain.

Finally, I went to the exhibition area at the rear of the museum, where I found some Hakka women's headscarves for visitors to try on (obviously geared for children). Sam Tung Uk is really starting to remind me of those pioneer villages (Todmorden Mills really comes to mind) that I used to go to on school trips back in Toronto!

Here are some biology notes written in ink and paper by a student training to become a teacher:

And some school texts dating back before the 1950s:

This exhibit was intended to show how politically diverse the Tsuen Wan population was in the 1950s: the pro-Communist side celebrates the October 1st National Day of the People's Republic of China in the upper photo while the pro-Nationalist side celebrates the October 10th National Day of the Republic of China in the lower photo.

In the same exhibition area, the Museum also had audio recordings of former Sam Tung Uk residents recalling stories of their childhoods. Their accounts painted a very vivid picture of a happy, communal childhood working in the fields alongside regular school work. Then, with encroaching urbanization, the villagers were suddenly displaced from their fields and migrated towards the "private" textiles and electronics factories (the old man who told this account seemed to emphasize that they were "private", possibly to contrast with the old "communal" village life. Eventually, the villagers were forced from Sam Tung Uk and resited in a modern village indistinguishable from other Hong Kong residential buildings. I found the story of Sam Tung Uk to be a sad one marked by the loss of innocent village life and assimilation into the fabric of an expanding urban Hong Kong. Today, the museum exhibits note that the rice fields of the past have disappeared from Hong Kong - the little agriculture remaining consists of small vegetable plots and flower gardens.

This is a shot of Clear Water Bay that I took while walking back to my student residence - the ships look like little lanterns in the water from here.

I also bought two excellent dictionaries from the 三聯書局 (Joint Publishing HK) near Tsuen Wan Station - one is a dictionary of 成語 (Chinese four-character idioms) with pronunciations in both Hanyu Pinyin for Mandarin and IPA for Cantonese; the other is a dictionary for 文言 (Classical Chinese) with both Mandarin pronunciations (pinyin and bopomofo) and Cantonese pronunciation (IPA).

This was a long post...see you next time!